Welcome !

Welcome to this special end-of-year edition of the STS Newsletter by PCS, keeping stakeholders up to date about market and regulatory developments in the world of STS.

In this edition we do not follow the usual pattern of our Newsletter but will instead look back at the year 2020, assess the current state of play and look towards 2021.

As ever, we very much welcome any feedback on this Newsletter.

Market data – Looking back at 2020 – What the numbers tell us about STS

Introduction

There can be no doubt that 2020 was the year of COVID-19 and the pandemic weighed, directly and indirectly, on all aspects of our lives. STS securitisation was no exception. We look at STS numbers generally and by asset-class and jurisdiction and attempt to draw out the big picture and emerging trends. We also look at our predictions for 2021.

Please note that, differently from most year-end commentaries, we have focused on number of deals rather than volume of issuance. The reason for this is not that numbers have a greater explanatory power than volume but rather that they have a different and complementary explanatory power. Many research firms and other commentators provide the volume numbers and it seemed of limited value to just do the same. But by focusing on numbers PCS hopes to shed not a better light but a different light on 2020. An example of this difference in perspective would be Dutch RMBS, where the volume decreases were driven by the (temporary?) withdrawal from the market of the largest issuers by volume. However, when one looks at the numbers, one sees an increase in smaller transactions by smaller platform players. That is the type of development that can be missed if one solely looks at the volumes. Also, a small number of very large transactions can distort the picture. A week ago, for example, ING issued a € 14bn retained RMBS out of its Spanish branch. This alone will add massively to the 2020 issuance.

(All numbers are as of 6th December 2020 and so comparisons with 2019 are not exactly on the same basis. PCS only expects 4 to 5 additional STS deals by year end though).

The big picture

Numbers

Numbers…

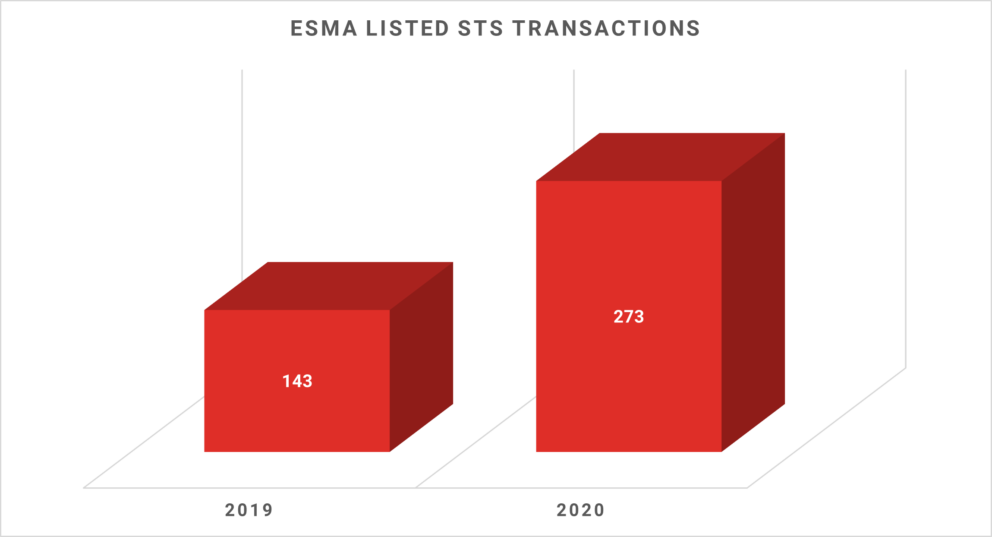

| 2019 | 2020 | Total | YoY | ||

| ESMA listed STS transaction | 143 | 273 | 416 | 90% |

Commentary

- With over 400 STS transactions registered, despite fears expressed in 2018, the STS standard is achievable for most “traditional” types of securitisation.

- Originators issuing in all asset classes that can achieve STS in a straightforward manner have universally elected to do so when publicly placing paper in the markets. The only exception remains “Buy-to-let” RMBS – almost entirely a UK and now Dutch product – where STS is not sought. This is usually attributed to the fact that BTL-RMBS is not eligible for the Liquidity Cover Ratio (LCR) pools of bank investors. With that exception, all publicly placed STS eligible securitisation is STS.

- Securitisations which are issued to be used as collateral with central banks (“retained transactions”) may or may not seek the STS. This is because neither the ECB nor the Bank of England have STS as a requirement in their collateral rules.

- 100% of STS securitisations publicly placed with investors in 2020 elected to be verified by a third-party verification agent (“TPVA”). A number of retained transactions also elected to do so.

- Over 95% of all publicly notified STS securitisations in 2020 (including retained transactions) elected to be verified by a TPVA.

Below the surface

Numbers…

| 2019 | 2020 | YoY | |

| Public | 104 | 81 | -22% |

| Private | 39 | 192 | 392% |

Commentary

- The five-fold increase in private transactions hides a 22% fall in the number of public transactions notified to ESMA as STS. This, though, is not an STS phenomenon but reflects a general decrease in securitisation issuance from € 90 bn in 2019 to € 75 bn in 2020.

- The decline reflects, in our opinion, the impact of COVID on the securitisation market generally. This impact was two-fold. First, but maybe less important, a slow down in retail borrowing at the onset of the crisis meant warehouse facilities filled up more slowly and funding requirements overall looked less substantial. Secondly, and in PCS’ view more impactful, central bank monetary policy drowned the banks in free liquidity. In these circumstances, fairly expensive securitisations find it difficult to compete with free cash for the heart of bank treasuries.

- Monetary policy will explain why the largest reduction in issuance yoy is from the traditional banking world, leaving as anchor issuers in the STS space (i) banks that have a long-term strategic focus on and commitment to securitisation despite the short term cost impact; (ii) financial institutions such as auto-captives that have placed securitisation at the heart of their business model and (iii) new challenger platforms that have also done the same. This does not mean there has been no STS issuance from more traditional banks, but it decreased substantially in 2020.

- After a blow-out at the beginning of the crisis, secondary market spreads started to tighten almost immediately and steadily in all jurisdictions and asset classes to return by mid-September to pre-COVID levels pretty much everywhere. Since then in some asset-classes, such as German auto’s, spreads have come inside of their pre-COVID levels. This is the clearest indication that the issues with STS issuance volumes were supply and not demand driven.

- Of the 192 private STS securitisations notified to ESMA, 174 were ABCP transactions. This number needs to be understood though and two points must be borne in mind. First, the STS Regulation requires that each conduit wishing to obtain STS status for a transaction must notify ESMA separately. So, if an originator has a transaction funded by 5 conduits, even though this is a single ABCP securitisation transaction, it will have to be notified 5 times to ESMA. Since ESMA does not publish any information on ABCP STS notifications, it is impossible to determine how many actual securitisation transactions are reflected in that 174 number. Secondly, differently from term transactions, ABCP transactions usually go on for many years with annual or bi-annual amendments reflecting changing circumstances. What we saw in 2020 were conduit sponsors using the opportunity of these amendments to make their ABCP transactions STS. Therefore, these 174 ABCP transactions do not represent new deals or new funding. The vast majority are transactions that have been existent for sometimes decades but are converting to the STS standard this year. Also, the small number of ABCP transactions last year reflected the fact that conduit sponsors had been granted a one year grace period before having to apply the new capital requirements to their conduit liquidity facilities. This meant that STS benefits only started for sponsors on 1st January 2020 rather than 1st January 2019 when they kicked in for everyone else.

Asset classes & Jurisdictions

| Public Transactions | 2019 | 2020 | YoY |

| RMBS | 50 | 28 | -44% |

| Auto | 44 | 31 | -30% |

| UK | 42 | 23 | -45% |

| Dutch | 16 | 7 | -56% |

| German | 18 | 12 | -33% |

Commentary

The sample of figures above confirms the overall picture. In both the UK and the Netherlands, a large part of the issuance is usually from traditional banks and most often in RMBS. In 2020, one of the two largest Dutch issuers (Obvion) stayed away from the markets post-COVID and the other (Aegon) stayed away in 2020 altogether. (Also, some smaller regular issuers like Argenta and EDML were missing in the public market.) Similarly, in the UK there was almost no post-COVID issuance from traditional bank and building society RMBS issuers. In Germany though, where auto-captives play a larger role and have built their business models around securitisation, declines were more modest. In the Netherlands though, the volume decline is more stark than the numbers since the large deals from traditional banks have been replaced in part by smaller deals from new platform entrants such as MeDirect.

Predictions

Predicting markets at the best of times is somewhat of a foolish endeavour. Today, with uncertainty over a global pandemic hanging over everything, it is truly quixotic. Yet, predictions are a traditional part of the holiday season, like Christmas trees, presents and over-eating. So here we go …

PCS continues to believe that the most important driver of subdued issuance remains the competition from central bank free money. Without any special knowledge, we assume that the current consensus view that the vaccines will be rolled out to a sufficient level to put restrictions on economic activity behind us by April/May is correct. However, central bank – and particularly the ECB still bearing the scars of its premature tightening in 2011 – are exceedingly unlikely to change monetary policy before well into 2022. A research house we recently spoke to, believed that no central bank tightening will occur until 2024.

So, based on our conversations with market participants and our own transaction pipeline, we see current ongoing volumes of issuance remaining steady for the first half of 2021. Once economic activity returns post-vaccine an acceleration of lending to consumers will, on the one hand, fill up warehouse facilities faster and, on the other hand, lead traditional lenders to want to dip their toes back in the water. But the free central bank money will still cast its baneful influence on issuance volumes. So, we expect some growth in the second half of 2021 but nothing spectacular.

One aspect that could add to issuance though is the growing interest by banks in deconsolidating securitisations. These are securitisations that allow the originator to free regulatory capital under the Capital Requirements Regulation. After their almost complete disappearance in the last two decades, such transactions are starting to re-appear with the looming threat of Basel III. Free money from central banks does nothing for your capital requirements and so this type of STS transaction should not suffer from it.

Taking capital relief deals and greater funding needs in 2H21 together, PCS expects the STS term market to grow a little over 2020, by about 15%.

The trajectory of ABCP STS notifications is harder to ascertain, since, as we have indicated above, most of these new STS notifications are not new deals and so the decision to amend them to STS or not involves more complex and also more private considerations over which it is harder to obtain visibility. PCS suspects that ABCP notifications might run at roughly the same rate as in 2020 before dipping in 2022 when all the existing low hanging fruit have been picked and STS ABCP will have come mostly from new transactions.

None of this takes any account of any possible STS synthetic market, as to which, we invite you to read our synthetics article below.

Synthetic STS – Quo Vadis ?

Background

In the STS Regulation passed in 2017, European legislators explicitly closed the door to STS synthetic securitisations. Yet, they also signaled that if the door was closed, it was not locked and instructed the European Commission to bring to the Parliament a project for incorporating such securitisations into the STS regime. Following a report commissioned by them from the EBA and published in May of this year, the Commission prepared some draft legislation which was presented to the European Parliament and European Council for expedited treatment. As this Newsletter is published, the draft legislation that would allow synthetic securitisations to become STS is being negotiated between the Commission, the Parliament and the Council and there is a decent chance that a political agreement could be reached before year end. In turn this would see synthetics become eligible for STS status already in Q1.

What is at stake ?

Upcoming reforms in the calculations for mandatory regulatory capital for banks (Basel III and additional European elements) and the impact of the leverage ratio is likely to put great pressure on European financial institutions to raise substantial new capital in, what were even before COVID-19, difficult conditions.

Therefore, tools that allow banks to manage their capital requirements by legitimately removing risk from their balance sheet have become a key element of the future of banking in Europe. Synthetic securitisations are one such tool.

But they suffer from a problem resulting from the anomalous and often logically inconsistent regulatory treatment of securitisations. A bank has a pool of assets. Those assets require capital to be allocated against them. To reduce that capital, the bank will “insure”, via a synthetic securitisation, some of the risk of that pool. This transferred risk may well be the risk for which 100% of the regulatory capital is required. But, after transferring some of the risk, the senior part of the risk that is not transferred is now treated as a securitisation AND the same risk in securitised form is treated much more severely than in its raw state. The result is that the capital usually required by that senior part of the risk AFTER all the real risk has been insured is often no less (and in some cases even greater) than the capital required before the bank removed that risk.

Allowing synthetic securitisations to be STS is a way to mitigate this absurdity. It will do this by allowing senior risk in retained synthetic STS form to attract the lower STS capital required by the CRR.

Will it work ?

Although the Commission could have done this by creating a new synthetic standard with benefits similar to those that exist for true sale securitisations for investors, they chose to follow the EBA’s lead and limit any benefits solely to the originator holding the senior tranche for capital reasons. In other words, the proposed law can only benefit banks seeking to manage their capital requirements.

PCS sees two problems with this approach. First, it is a missed opportunity to create a new investor standard that could have been the seed of a new class of tradeable securities. This would have improved the prospects of the European Capital Markets Union (“CMU”). Policy makers focused more on fixing the mistakes of the past than on building the future.

Secondly, although policy makers opted to limit the scope of the legislation solely to originators holding the senior piece, they then added provisions which, in fact, go against the interests of the same originators and make it more difficult to execute this type of securitisations. This would have made sense if they were creating an investor standard but they chose not to do this. A good example of this are the discussions around cash collateral and how it should be taken away from the originator in yet to be settled circumstances. In this, the proposed law seems to be working at cross-purposes.

Another potential problem is the issue of synthetic excess spread, where sensible EBA proposals appear to have become somewhat of a political football and where we cannot exclude a fairly bad result.

Will we have synthetic STS securitisations in 2021?

It seems probable that some political deal will be struck this year or early next year. This would, in theory, see STS synthetics become available early in 2021. A question mark though will be how the synthetic excess spread and cash collateral debates end up. In particular, and especially for the former, it is possible that the can will be kicked down the road by devolving the final decision to an EBA drafted regulatory technical standard. Depending on when that standard is passed and the level of uncertainty as to where the EBA will come out, it is possible that some or many banks will postpone doing STS transactions. This is hard to predict though. The delay in the passing of the “homogeneity” RTS for true sale securitisations did not thwart issuance in early 2019. But that was also because the market had a fair sense of where the EBA would come out on the issue.

What about STS synthetics in the UK and Brexit ?

PCS did a lengthy piece on this which can be found here.

Summary: there will be no synthetic STS securisations in the UK unless the UK government passes legislation to that effect. The chances of this are fairly small at this juncture.

Brexit and STS

Barring extraordinary developments – which in 2020 can never be entirely discounted – the UK will truly exit the European Union on 31st December 2020, at midnight Brussels time.

So where has the tortuous exit process, at times pure slapstick comedy, at times horrifying road to Golgotha, left securitisation and STS in particular?

First, one must recognize that whatever final deal is struck over fish and chocolate, for the finance industry, Brexit was always going to be a “hard Brexit”. Many clear-eyed observers have long considered that the UK’s request to protect the City of London by covering broad swathes of the financial industry with “equivalence regimes” was not so much optimistic as what American sports aficionados call a “Hail Mary”. For reasons unconnected to Brexit, EU policy makers have, over the last few years, become very wary of “equivalences” in financial regulation. For them to grant extensive equivalences to the City of London would have required them to overcome that skepticism. Such a reversal, in turn, would have called on an immense amount of political goodwill. The type of political goodwill that the UK government, seemingly wedded to triumphalist declarations, not so much squandered as drenched in kerosene and set alight.

Securitisation was no different. Despite some concessions from the UK, the STS regime will basically suffer a total fracture running down the Channel.

This article summarises the position of STS securitisation in the new year. For those wanting to delve deeper in the arcana, we also provide the links to the relevant texts – in red highlights.

Legislative background

On the UK side, the legislative rules that regulate Brexit are set out in a UK Act of Parliament: the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020. Under this act, Her Majesty’s Government can pass statutory instruments to regulate diverse parts of the UK legislative landscape in the implementation of Brexit. Such an instrument was passed to amend the EU securitisation regulation: the Securitisation (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019. This is our key document and will be referred to as the “UK REG”.

The UK Securitisation Regulation: what it does and does not do

General purpose

The main purpose of the UK REG is to onshore the STS Regulation. In other words, the UK REG makes all the logically necessary changes to jurisdictional clauses.

So, “EU” in the STS Regulation is replaced by “UK”, “ESMA” by “FCA”, “EBA” by either “FCA” or “PRA”, references to specific EU legislation by their new UK replacements and so on.

What is unchanged?

- The STS criteria – these remain exactly the same for both term transactions and ABCP

- The role of Data Repositories

- The role of Third-Party Verification Agents

- The notification requirements for STS (but to a new FCA website)

- The disclosure requirements for UK issuers (but not non-UK ones)

- The ban on re-securitisations

- The risk retention requirements

What is changed?

- Disclosure obligations for third country originators

- The UK REG makes explicit that non-UK originators and sponsors do not have to comply with the Article 7 disclosure requirements in exact detail. This is ambiguous in the existing EU STS Regulation and the European Commission has never clarified whether non-EU originators and sponsor had to comply with Article 7 or not (despite many requests for such clarification).

- This change is made by the UK REG amending Article 5 requiring investors to ensure that Article 7 disclosure is complied with and replacing it, in the case of third countries (including, of course, EU countries), with the unambiguous obligation to ensure only that substantially similar disclosure is achieved.

- Non-UK SSPEs for STS

- Whereas, to obtain STS status, the EU STS Regulation requires that the originator, sponsor and SSPE be in the EU, the UK REG removes any territoriality requirement on the SSPE.

- Therefore, for UK STS, the SSPE can now be located anywhere in the world. But, for UK STS, the originator and sponsors now must be in the UK and no longer, as before, anywhere in the European Union.

- Grandfathering and transition of EU STS in the UK

- The new UK regime provides that all EU securitisations notified as STS to ESMA before a date falling two years from the end of the transition period (i.e. 31st December 2020) will still be considered STS in the hands of UK investors. This is both a grandfathering of EU STS transactions issued on or before 31st December 2020 and a set of transitional provisions for EU STS transactions issued and notified after the new year but on or before 31st December 2022.

- To be clear though, this does not cover UK STS transactions issued before the end of the year and notified to ESMA. This is because, to benefit from these grandfathering provisions, a transaction must continue to be on the ESMA website list. On 1st January, UK transactions will be removed from that list – as to which see below.

- What about rules and guidelines?

- Under the Withdrawal Act, all legislative rules in force at midnight Central European Time on 31st December 2020, will be part of the laws of the United Kingdom unless specifically changed by the UK at a later date.

- Regulatory Technical Standards passed before that date (such as the homogeneity RTS) will therefore remain legally binding on UK originators structuring STS transactions.

- Rules and guidelines that are not legally enforceable – are not “legislative” in nature – will cease to have any force in the UK. These would include the EBA guidelines under the STS Regulation.

- However, to avoid chaos, the Bank of England and the PRA have issued a joint statement stating that they expect all regulated firms to continue to apply EU rules and guidelines unless specifically overruled or irrelevant post-Brexit.

- Based on that statement, the EBA guidelines on STS interpretation (which, under the STS Regulation are not legally binding even within the EU) should continue to be deferred to when interpreting criteria unless and until overruled by the FCA.

So what does this mean in practice?

- UK transactions and ESMA

- As of 31st December 2020, UK originators/sponsors will have to notify ESMA that their securitisations no longer meet the STS requirements – specifically as they do not meet the Article 18 requirements for an EU originator or sponsor. This notification is an obligation under Article 27.4 of the STS Regulation, not a suggestion.

- That said, based on our reading of the statement of the Joint Committee of the ESAs, whether UK originators or sponsor do notify ESMA or not will make no meaningful difference since the statement indicates that ESMA intends to remove all UK transactions on 1st January 2021 anyway. From that moment, EU based investors will no longer be allowed to treat these transactions as STS and will have to apply to them the higher capital requirements mandated by the CRR (for banks) or Solvency II (for insurers) for non-STS deals. EU banks holding such transactions in their LCR pools will have to remove them. There are no grandfathering or transitional provisions for EU investors.

- Existing UK transactions and the FCA

- UK investors cannot treat a UK transaction as STS from 11.00 pm (London time) on 31st December 2020 unless that transaction appears on the new FCA website. The FCA, helpfully, set up that website on November 23rd so that UK originators and sponsors may start to pre-populate it before the end of the year.

- Please note, that the obligation to notify the FCA via the FCA website appears to be that of the originators and sponsors. There will not be an automatic transfer from ESMA to the FCA. We understand that the FCA has reached out to all UK STS originators to inform them of the new rules,

- Information on the FCA process, how to upload to the FCA website, called Connect, the templates and other information can be found on the relevant page of the FCA’s website.

- Existing EU transactions and the FCA

- As we have seen, all EU transactions notified to ESMA before 31st January 2022 can still be treated as STS in the hands of UK investors. To be clear, this means historical transactions notified before the end of the Brexit transition period and future transaction notified between January 1st, 2021 and December 31st, 2022.

- So long as these transactions have not been removed from the ESMA list, they will continue to be treated as STS in the UK for their whole life, not just till December 2022.

- Third-Party Verification Agents (TPVA)

- As the FCA ceases to be an EU national competent authority on 1st January 2021, no TPVA authorised only by the FCA can verify an EU STS securitisation from that date.

- PCS EU, being authorised in France by the AMF, will continue though to be able to provide verification to all EU STS transactions.

- Also, since PCS UK was authorised throughout the EU before that date, all transactions verified by PCS UK prior to 1st January 2021 will remain validly verified under EU law. (This is no different than if PCS had decided to wind itself up or had lost its authorisation at some point. Neither of these occurrences would affect past valid verifications).

- Only TPVAs authorised by the FCA will be allowed to provide verifications as defined in UK law for UK STS transactions as of 1st January 2021.

- As re-notification to the FCA of transactions that have already been notified to ESMA are not “new notifications” dated as of the re-notification date, but transcriptions or refiling of existing notifications following Brexit, no new PCS verification is required upon the notification of existing transactions to the FCA.

- Data Repositories

- Currently no Data Repositories are authorised anywhere in Europe and so originators and sponsors can post information in accordance with the transitional rules provided for in the STS Regulation. These allow data to be made available on any website meeting certain basic requirements.

- From 1st January 2021, this situation will continue until at least one Data Repository is authorised. But this requirement is now doubled and separated on each side of the Channel.

- So UK originators whose transactions are listed as STS on the FCA website, can continue to post data as they currently do until a UK Data Repository is authorised by the FCA. The authorisation of an EU Data Repository by the ESMA will have no impact on this obligation. In other words, UK originators with UK STS transactions can continue, until the authorisation of a UK Data Repository, to post in the current manner even after the authorisation of an EU Data Repository. (They can also choose to post with that authorised EU Data Repository if they wish, but for UK purposes, that entity will not be a “Data Repository” but only a website that meets the basic requirements of the law.)

- Exactly the same applies to EU originators who can continue to post as they currently do until an EU Data Repository is authorised and are equally unaffected by the authorisation of a UK Data Repository.

- Cross-Channel Risk Retention

- A possible source of complexity exists to current transactions where there is a cross-channel risk retention. This would be the case when an originator sought the benefit of the existing rules allowing risk retention on a group basis but where the retention holder was in the UK for an EU STS transaction or in the EU for a UK STS transaction. Such cross-channel risk retention structures would not seem to survive Brexit.

5. PCS – people in numbers

In this Newsletter, we will not highlight one of the members of the PCS team as usual but mention some things you probably did not know about the Outreach and Analytical team at PCS :

- number of members in the teams: 8

- number of nationalities represented: 6

- last job before PCS: rating agency (2), investment banking (3), general banking (2) law firm (1)

- average shoe size: 42 (EU)

- average years working in securitisation: 25 years

- average height: 1.83 m

- average number of languages spoken by each team member: 2.9.